LOCATION SCOUTING IN “KORBAN FITNAH” (PART 1)

Film Title: Korban Fitnah

English Film Title: Victim of Slander

Directed by P.L. Kapur (pseudonym of respected Indonesian film director Usmar Ismail)

Screenplay by Ralph Modder

Produced by Maria Menado Productions and Cathay-Keris Studios

Year of Release: 1959

Film Synopsis: Hussein is led by a group of policemen as he exits a prison compound, and is escorted to the District Court on a police jeep. He is to face trial for attempted suicide. After being pursued by the judge, he finally relates how he had decided to commit what is deemed as a criminal offence in Singapore. The film then goes into a flashback that reveals, among many other things, that Hussein is unfairly suspected by his brother Hassan of having an affair with his sister-in-law Rahimah. Hussein and a pregnant Rahimah are then thrown out of the house. Hassan eventually realises that he was in the wrong and had been misled into believing that his brother and his wife are committing adultery. He goes in search of the pair and unfortunately meets with a car accident that results in his loss of sight — which leads Hussein to attempt suicide to save his brother.

The Film Locations:

Despite the rather clumsy plot, with the most absurd of coincidences happening at many junctures, the film is still noteworthy for its portrayal of the urban landscape of Singapore in the late 1950s. (There are a number of shots of Kuala Lumpur as well.) Location shooting is aplenty in the film, which depicts places — especially those that are no longer around today — such as the Outram Prison, the District Courts at Hong Lim Green, Wyman’s Haven Restaurant along Upper East Coast Road, old C.K. Tang building, Bedok Restaurant, Singapore Hotel and the former coastline of eastern Singapore before land reclamation.

Due to the numerous locations that the film has depicted, I surmised that I will require a few blog posts / parts to write adequately about them. Most of the places are not in existence today, so I thought it would be worthwhile to uncover more information and related events with respect to these lost places. Part 1 will concentrate on the Outram Prison and Pearl’s Hill. Part 2 on the District Court and Hong Lim Park. Part 3 on restaurants, hotels, places for leisure and the hospital.

1. Outram Prison at Pearl’s Hill

As described in the synopsis above, the film opens with a compelling sequence that includes shots of the Outram Prison compounds and a drive through the Singapore city center, taking in the vicinity of the prison at the foot of Pearl’s Hill, Keppel Road, the Customs House, Cantonment Road, Fullerton Road, Anderson Bridge, before arriving at the Criminal District and Magistrate Courts at Hong Lim Green along South Bridge Road. I have uploaded an excerpt of the opening sequence on Youtube. The song that accompanies this sequence is “Burung Dalam Sangkar”(translation: Bird in a Cage). More information about the song can be found on the Youtube page.

As depicted in the film excerpt, Hussein is led out of the prison by a group of policemen, and the audience is presented with shots of the interior and immediate exterior of the Outram Prison, which was located at the foot of Pearl’s Hill. The prison began as a small civil jail constructed in 1847 by Captain C E Faber (Mt. Faber is named after him). It was later expanded in 1882 by Major J F A McNair to accommodate criminal prisons as well, and that was the prison complex which the film depicted in 1959. So, it was an almost eighty-year-old institution when the film was shot there. The prison was also significant for having held political prisoners during the Japanese Occupation and during Operation Cold Store in 1963 (more on this later in the post). It was finally demolished in 1968 to make way for a new HDB public housing project — Outram Park Complex, which in turn was torn down in 2002 for future redevelopment. The site of the former prison grounds remains empty for now.

.

Film-stills from “Korban Fitnah”. Interior of the Outram Prison complex.

.

Film-stills from “Korban Fitnah”. Exterior of the Outram Prison Complex in 1959. The police jeep exits from the rear entrance, travels along a road behind the prison (which is probably where a road named “Outram Park” is today), exits at a gate just before the road turns downhill, and drives down towards the roundabout where the prison’s front entrance is.

.

An aerial photo of the vicinity of Outram Prison, 1950s. The area shaded in red is the Outram Prison. The orange-red line roughly follows the route that the police jeep took in the opening sequence of “Korban Fitnah” — from the rear entrance behind the prison, down towards the roundabout and out onto Outram Road.

Other notable buildings and installations are highlighted as well: green – Pearl’s Hill Reservoir; orange – Outram Secondary School (now redeveloped as Outram Park MRT Station); yellow – probably Prison Warders’ Quarters (or later Outram Primary School?); blue – Pearl’s Hill Police Quarters (later the Police Operational Headquarters).

.

Aerial view of Pearl’s Hill and the Outram Prison in 1964.

.

Detail from a 1935 map published by Yellow Top Cabs. The Outram Prison and its vicinity.

The red oval marks out the Outram Prison, otherwise known as H.M.Prison (Her Majesty’s Prison). The green line traces the route the police jeep took in the opening sequence of “Korban Fitnah”. The orange circle marks out the destination of the police jeep in the film, the District and Magistrate Courts next to Hong Lim Green. Apparently, the jeep took a detour around Keppel Road and Fullerton Road. It could have travelled along New Bridge Road, a more direct route. But then, we, the audience, would have been deprived of a little glimpse into the cityscape of 1959 downtown Singapore.

…

As mentioned above, besides being a criminal prison and later a remand prison after the establishment of Changi Prison in 1936, the Outram Prison was also used to hold political prisoners or prisoners of conscience during different eras in Singapore’s 20th century history. First of all, civilians — many of them Chinese, with communist-related links –were detained or executed in Outram Prison after kangaroo court trials during the Japanese Occupation 1942-45. After the World War II, the British colonial authorities also imprisoned Malayan nationalists such as members of Kesatuan Melayu Muda (KMM) and members of the Communist Party of Malaya (CPM, or MCP) in Outram Prison for political subversion. A few years before the prison was demolished, it was used to detain, without trial, many left-wing political activists in a major detention operation codenamed “Cold Store” — conducted during the dawn of 2 February 1963. (By the way, today, 2nd February 2013, is the 50th anniversary of Operation Cold Store!)

What follows is a compilation of quotes from books and articles that I have collated with regards to the history of Outram Prison, especially during its use for the detention of prisoners during Operation Cold Store. The numerous quotes would also be interspersed with images of Outram Prison, plans, maps and later developments of the site through the different eras.

…

Operation Cold Store and Outram Prison

.

“On 2nd February 1963 Lord Selkirk, UK Commissioner, Singapore, reported to the Secretary of State for the colonies:

‘Operation started at 02.15 hours. For security reasons arrest parties were assembled 30 miles inside Johore with co-operation of the Federation [of Malaya] police. Arrest parties crossed causeway at about 03.15 hours. By 09.15 hours, 97 persons had been arrested including nearly all the leading figures. Police hope that by midday, total arrests will be between 110 and 120. This is considered satisfactory, more will be picked up later” (CO 1030/1577 Singapore Internal Security Council Tel 77).’

“The ‘operation’ was Cold Store which threw 111 persons into jail. It was the time of the proposed merger — the British plan to form a new territory to be called Malaysia, comprising Singapore, Malaya and the two Borneo states of Sabah and Sarawak. […] Cold Store effectively destroyed the powerful Barisan Socialis [a major left-wing political party in Singapore] and its allies, and ensure the continued control of Singapore by the British.”

(Excerpted from Lim Kean Chye’s Foreword to Said Zahari, Dark Clouds at Dawn: A Political Memoir, INSAN, Petaling Jaya, 2001, pp.xxiv-xxv. Additional contents in square brackets mine.)

..

“3 February 1963 [sic] was a fateful day for the Barisan Socialis. It started with the decision of the Internal Security Council to launch a crackdown against what was described as the “anti-Malaysia elements” involved in a “giant communist conspiracy to launch attacks in Singapore in the event of the planned armed intervention by Indonesia in British Borneo” (Sunday Times, 3.2.1963). The premises of Barison Socialis, the Partai Rakyat Singapura [PRS], the SATU [Singapore Association of Trade Unions], group of unions and other “open front communist organisations” were raided from 3:00 a.m. and 107 [sic] people were detained. Among the “big names” taken into custody were Lim Chin Siong, S. Woodhull, Fong Swee Suan, James Puthucheary, Dominic Puthucheary, Dr Poh Soo Kai, Dr Lim Hock Siew, and Said Zahari (Ibid., 3.2.1963).

“The security swoop — dubbed “Operation Cold Store” — was decided after a meeting of the Singapore Internal Security Council held a day earlier, chaired by Lord Selkirk and attended by representatives from Britain, Malaysia and Singapore. The Singapore delegation included Lee Kuan Yew, Dr Goh Keng Swee and Ong Pang Boon (Ibid., 3.2.1963) and the operation was carried out by the Singapore police assisted by personnel from the Federation [of Malaya]. This was followed by other moves aimed at smashing a [supposedly] resurgent Communist United Front — such as the closure of a number of unions and organisations, and the banning of many of their publications.

“All the detainees were being held under the Preservation of Public Security Ordinance [the predecessor to the Internal Security Act or the ISA, still in use in Singapore today; it allows the government to arrest and detain individuals without trial for up to two years and renewable upon the Home Affairs Minister’s and President’s recommendations] and the Director of the Special Branch, George Bogaars, directed the operation (Straits Times, 3.2.1963 and 6.2.1963 and Sunday Times: 3.2.1963).”

(Excerpted from Hussin Mutalib, Parties and Politics: A Study of Opposition Parties and the PAP in Singapore, Marshall Cavendish International, Singapore, 2004, pp. 96-97. Additional contents in square brackets mine.)

..

Local News Headlines of Sin Chew Jit Poh, 3rd Feb 1963, a day after the launch of Operation Cold Store.

..

“Infamously code-named Operation Cold Store, more than 100 political activists were detained under draconian detention-without-trial laws in February 1963. This political cleansing was undertaken with the assistance of the British colonial authorities and the Malayan Federal government. The UMNO-dominated Alliance government feared the prospect of a potential Cuba at Malaya’s doorstep should the PAP [People’s Action Party, led by Lee Kuan Yew] lose power to the Barisan Sosialis — a breakaway left-wing nationalist party led by the charismatic Lim Chin Siong. The mass defection of activists from the PAP to the Barisan Sosialis left the PAP with not only a skeletal grass-roots support base, but also a razor thin majority in the island’s legislature. Approved by Whitehall, Operation Cold Store effectively saved Lee and the PAP government — dithering on the verge of collapse in the face of unrelenting opposition party sponsored motions of no-confidence against it. As Said [Zahari] notes, the British ‘needed conservative, pro-Western and anti-communist local leaders for their former colonies, namely Malaya and Singapore…. So for the benefit of the colonialists, LKY [Lee Kuan Yew] must be saved from Singapore politics. The PAP must be saved from destruction’.

“Operation Cold Store was justified on the grounds that the islands’ security was threatened by communists intent on gaining power through unconstitutional means. Said dismisses the validity of this assertion by reminding us that the Malayan Communist Party (MCP) was already a diminished force in the late 1950s, as evidenced by the official declaration of the Emergency’s end in 1960. Left-wing nationalist movements and political parties that were opposed to merger and threatened the longevity of the PAP government were thus prime targets of Operation Cold Store.”

(Excerpted from Lily Zubaidah Ibrahim’s foreword titled “Said Zahari – Demystifying Lee Kuan Yew’s Singapore Story” to Said Zahari, The Long Nightmare: My 17 Years as a Political Prisoner, Utusan Publications & Distributors, Kuala Lumpur, 2007, pp. xvii. Additional contents in square brackets mine.)

..

“As Duncan Sandys [UK Secretary of State for the Colonies] had already indicated, it was the situation in Brunei that provided the ‘best possible background’ for the arrest programme. On 8 December 1962 there was a popular uprising in Brunei led by A.M. Azahari’s Partai Rakyat [Brunei]. It emerged that Lim Chin Siong had met Azahari in Singapore on 3 December [1962]. The Barisan Sosialis, true to its anti-colonial stand gave moral support and sympathy to Azahari and the Partai Rakyat. Lee [Kuan Yew] told [Philip] Moore that there was now a ‘heaven-sent opportunity of justifying action against them.’ (Moore to Sec of State Colonies, CO 1030/1160, No. 572).”

(Excerpted from Poh Soo Kai, “Detention in Operation Cold Store: A Study in Imperialism” , in The Fajar Generation: The University Socialist Club and the Politics of Postwar Malaya and Singapore, Strategic Information and Research Development Centre, Petaling Jaya, 2010, pp. 189. Additional contents in square brackets mine.)

..

“The special meeting of the Central Committee of Partai Rakyat Singapura (PRS) on the night of 1st February 1963 in Bukit Timah Road ended around midnight. [Said Zahari had just been elected chairman of Partai Rakyat Singapura.] After a snack, we adjourned. Hussein Jahidin and I left in my Peugeot 403. […] We reached my house in Jalan Nyuir, Kampung Kebun Ubi, at about 1.00am.[…]

“About three hours later, I was arrested. So was A. Mahadeva, who was scheduled to leave for Jakarta with me at 10 o’clock that morning. Others arrested included Hussein, Wahab Shah, Pang Toon Tin, Salahuddin, Dominic, Chin Siong and over a hundred leaders of the Barisan Sosialis, Partai Rakyat, trade unions, Rural Residents’ Associations, Nanyang University and Singapore University graduates and undergraduates and a number of journalists with the Chinese-language newspapers. We were arrested in a large-scale operation covering the whole of Singapore, called ‘Operation Cold Store’. […]

“I was taken away by six Special Branch officers who had come in two cars escorted by armed Gurkhas in a military jeep, at dawn during the fasting month. Everbody was quiet in the car. In that silence, I suddenly remembered what Lee Kuan Yew had said to me at our encounter in the Parliament building over a year before: ‘Said, I think you should find appropriate employment, or else you may drift to the Barisan Sosialis or Partai Rakyat and make my work more difficult.”

(Excerpted from Said Zahari, Dark Clouds at Dawn: A Political Memoir, INSAN, Kuala Lumpur, 2001, pp.179-180. Additional contents in square brackets mine.)

..

The front entrance of Outram Prison in 1961.

..

“On that fateful morning of 2 February 1963, I was taken to the Outram Prison. Handcuffed like a common criminal, I was escorted by Inspector Hashim through a big door, passed through a series of sucessive small doors until we reached an area where there were several small tables. The officials were busy registering new prisoners. He left me there and I was transferred to the prison officer-in-charge. I was asked to stand in one corner to await my turn to be registered. […]

“Prison uniform was forced upon me though I was not a convict. That morning, I was not accorded any status. I was neither a convict nor a political prisoner because I had never been put on trial and a temporary detention court order was never issued. So what right did they have to take me as a prisoner and force me to wear a prisoner uniform. Deep in my heart, I was determined to challenge them.

“When I reached a small, thick and heavy door, my stone-faced escort, a heavy-set prison warden with a thick moustache, opened the door with a huge key. He turned it two or three times before it opened. I walked through the door. On my left, I immediately faced the first cell of the block. As I walked down the corridor, I glimpsed a young Chinese man in one of the cells. […] ‘Sai Jha-ha-liii….,’ he called me. […] I wanted to talk to him, but my escort warden nudged me to keep on walking. My friend called out my name in Mandarin repeatedly. […] The whole block was in a state of uproar. His calls were returned by other calls, and it went on until I reached my cell. The motive was to ‘welcome’ my arrival while introducing me to other friends who had ‘arrived’ earlier. That morning, Outram Prison was brightly lit, and there was a party-like atmosphere.”

(Excerpted from Said Zahari, The Long Nightmare: My 17 Years as a Political Prisoner, Utusan Publications & Distributors, Kuala Lumpur, 2007, pp. 33 & 36.)

..

Two of the numerous three-storey prison blocks in Outram Prison, 1950s. One small window to a prison cell. Cellular separation was the practice in Outram Prison.

..

“Then, I heard more loud sounds of clanging cell doors and shouts of names reverberating through the prison in a space of just a few minutes. The scale of the detention exercise dawned upon me. I looked around my sparse cell and all I saw was a small thin mat, a dark woollen blanket and a tin plate and mug. My intended question for the warden was answered when a sai tong (a dump bin, also made from tin, with a cover and two handles on its side) [‘Sai-tong’ is probably Hokkien for ‘shit bin’, ie. ‘屎桶’] caught my eye. I had never in my life ‘conducted my business’ in a sai tong. How would I wash myself? A quick glance and I saw a roll of toilet paper left at the side. I was disgusted at their ignorance for basic human decency.

“Outside my cell, the rambunctious atmosphere emitted anarchic noises like a fish market at Geylang Serai, with prisoners angrily voicing their frustrations at their loudest while some banged their sai tongs on the cement floor, in protest of their unjustified arrests.

“‘Ask them to shut up!’ ordered an officer with a loud voice. ‘Hey, shut up, shut up! Don’t make noise,’ a warden screamed. ‘Lu diam! (You shut up!),’ a prisoner retorted. Then, the other prisoners began to mock: “Lu diam… lu diam… lu diam…!’ in unison while banging their sai tongs on the cement floor, louder and louder. The others shook their cell doors and shouted political slogans.

“There was excitement crackling in the air and my heart pumped with adrenaline. No worries, no doubts and no fear. My spirits soared in the middle of this cacophony of insults and political slogans directed at the jailers.”

(Excerpted from Said Zahari, The Long Nightmare: My 17 Years as a Political Prisoner, Utusan Publications & Distributors, Kuala Lumpur, 2007, pp. 37. Additional contents in square brackets mine.)

Note: Said Zahari was one of the longest detained political prisoner in Singapore, having spent a total of 17 years under political detention without trail. His incarceration in Outram Prison was about a week long before he was transferred to prison cells in the Central Police Station and later to Changi Prison.

..

Demolition of Outram Prison in phases. 1963. A cleansing of sorts.

..

“I [Poh Soo Kai] was therefore picked up, like my colleagues, in the wee hours during the pre-dawn sweep. There were fierce barking of the dogs, swarm of fully-armed Gurkha police, the jeeps and the land-rovers. I was taken to Outram Prison together with most of the 100 or so detainees, to be locked up in solitary confinement for months. A covered tong for toilet and another aluminium container for water. The cell though small and with no windows was surprisingly well ventilated by angled slits in the thick wall. There was no reading or writing material.

“Oddly, I desperately tried to keep my sense of time. I suppose I was so used to consulting the clock in my daily work. The hours could be roughly gauged by the doling out of food and officers’ rounds. But the long days were different. Have I been in for 15 days or is it 20? This was the start of the long years of privation for the 100 or so detainees. The anguish due to separation from family and friends, of attempts by special branch officers seeking to break up marriages and relationships, of family members having difficulties in finding employment, made for mental breakdowns. Many were physically tortured. Not a few went mad. Almost all suffered from what today would be called post-traumatic stress syndrome. There was a total lack of information of the world outside. Even the local press was supplied with all economic and political news blackened with non-washable printers’ ink.

“As Lee Kuan Yew himself recently recognised the detention regime initiated after Operation Cold Store was deliberately the worst of its kind: ‘The biggest punishment a man can receive is total isolation, in a dungeon, black and complete withdrawal of all stimuli. That is real torture. (Lee Kuan Yew, January 2008).”

(Excerpted from Poh Soo Kai, “Detention in Operation Cold Store: A Study in Imperialism”, in The Fajar Generation: The University Socialist Club and the Politics of Postwar Malaya and Singapore, Strategic Information and Research Development Centre, Petaling Jaya, 2010, pp. 194-195. Additional contents in square brackets mine.)

Note: Poh Soo Kai was the assistant secretary-general of the Barisan Sosialis when he was arrested and detained without trial during and after Operation Cold Store. He suffered two lengthy periods of political imprisonment totalling 18 years.

..

An uncredited photo of the demolition of Outram Park HDB Complex in 2002. Yet again, the future of the site of former Outram Prison and former Outram Park begins on a clean slate, in this country that pays too much attention to what lies ahead and inadvertently abandons its history. Forging ahead towards an isolation from its history.

..

Outram Park Housing Complex (in the foreground) when it was newly completed in the 1970s.

..

“咦!前面不是欧南监狱吗?我明白了!英国人建的监狱,是建给反英的人住的,今天,我有资格住进去了!

”监狱大门打开了,哗!像走到了街市一样,闹哄哄的,有无数个熟悉的身影,被自己的政敌投进监牢!(…)我向远处熟悉的人群微笑,点头,挥手打招呼,原来有许多人比我更早‘报到’了。我看到自己工会的会务顾问方水双,人民协会的秘书汪永祥,巴士工友联合会的秘书陈世鑑… 像菜市一样的人潮,声音杂乱。这是英,马,新联合大镇压底下的奇景!是他们的‘枪杆子里保政权’的杰作!(…)

“我跟狱卒走进了一间高大多层,长形的建筑物,中间有张木桌,几条板凳,两边有很多房间,有的锁着门,有的打开着门,门上有一个只能容纳一只眼睛看进去的小洞。我抬头看,楼高多层,每层的上空有铁网隔着。(…)

“房门紧锁后,我要做的第一件事,先检查一下自己的房间。我把左右手一字形伸开,两手的指尖触到两边的墙壁,估计大概是六尺宽;中间摆放着一张铁的单人床,是嵌在水泥板上的,床尾与门之间还留下一点空间,估计房间的长度是八尺左右。床上放着两条劣质的单人被,两条‘祝君早安’的单薄面巾,一个上六寸宽,下四寸阔,约十寸高的铝杯,还有一个比水桶大得多的,像饭锅有盖的铝质产品。(…)床头的上端,靠近天花板处,有一个手不可攀的,被铁网紧封的小窗口,床头底下,两边的墙角各有一个约两寸宽,四寸高的阴暗小洞;牢房的门是密封的,它的低端有好些以粗铁网焊死像蜂窝般的通风小洞。这就是我的‘新世界’。”

(摘自 吴静明,《走不到终点的人》,新加坡,2010年2月, pp.76-78.)

..

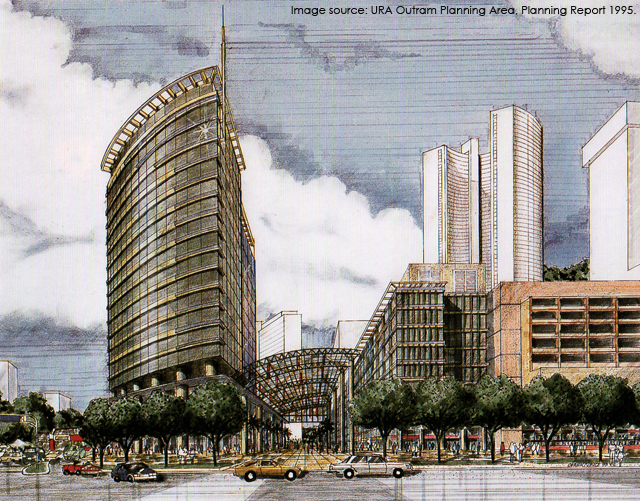

URA’s 1995 plan for possible future development above the current Outram Park MRT Station. Anticipation for another shopping mall-cum-“premium”-condominium mixed-use building project.

..

“‘洗澡,不准讲话!’ 狱卒又打开牢门,带着警告地还我一丁点的自由。接着以同样的方式打开我左边的门,被关的是人民党的副主席冯俊田,然后是商行的甘绍仪,《民报》的陈再聪,社阵的林清祥,(…)这个时候,我看了一看自己的门口上端,刻着47-A,被关了一昼夜之后,才知道自己的准确位置。(…)

“在欧南监狱度过了六十八这天种生活,大家和我却是相见不相识。十个半月后去上诉庭时,在樟宜监牢的大厅遇到两名被捕后第一次见面的泛星中委MW和JP,太高兴了,我向他们点头示意,呼唤他们的名字。反应只是望了一望我,没有手势,没有声音,一个敢叫,两个不敢应,变了个样。六年半之后,我计算了一下,在十七个同天从欧南监狱调去樟宜监狱的人当中,只剩下我与何标两个人时,我认识了一个问题:许多为了共同的目标而奋斗,被投进监牢的人,又会为了种种不同的目标而各自走出监牢!这就是政治,是残酷的现实,每一个因为政治而坐牢的人,都得面对和接受这种转变。

“政治犯是善变的,许多人进去时一个样,出来时又是另外一个样。如何去认识这个‘前样’和‘后样’,对于自己也是一种考验。用‘前样’度‘后样’,未必有正确的答案。因为用同一把尺去衡量一个生活在两个不同时期的同一个人。我们对于出狱的人应该有一个重新认识的过程。”

(摘自 吴静明,《走不到终点的人》,新加坡,2010年2月, pp.80-81.)

注:吴静明 Ng Cheng Weng(1936~2007)出生在新加坡。在马来半岛丰盛港亲历抗日,抗英的苦难岁月,于1957年返回新加坡,投身职工运动,担任过泛星各业职工联合会(SGEU;Singapore General Employees‘ Union)第一,第三分会的领导工作,兼任泛星的中央副总务。1963年“二二”系狱(Operation Coldstore 2 Feb 1963),坚韧不屈,十一年后却被强加条件释放。四年后(1978)再度被捕,罪名是触犯‘限制令’。

..

Where once stood the Outram Prison and Outram Park Housing Complex…

城市也是善变的… 始终都得面对和接受转变…

..

“As interrogations of detainees slowly progressed, the methods came under scrutiny. Behind the medical and sanitary metaphors in which the arrests were cloaked, a harsher picture began to emerge. One lawyer, representing Nanyang University students, reported that he was unable to see his clients until 5 March [1963], during which time they were in solitary confinement. ‘It seems that the whole purpose is to destroy the mental balance of these young university students’. He found one of the woman detainees on the verge of mental breakdown, suffering from acute insomnia, serious lack of appetite and living on sleeping tablets supplied by the prison medical officer since the day of her detention. He claimed that ‘force and threats of force are applied on students who are to them “non co-operative”‘.

“Lord Selkirk was alarmed by a statement by the Federation Special Branch at a meeting in Kuala Lumpur that it intended to keep ‘hard core detainees’ in solitary confinement ‘indefinitely, as experience showed that after about eighteen months this brought about the psychological changes necessary for rehabilitation.’ It was, Selkirk added, ‘not improbable’ that Singapore had a similar policy and challenged the policy at an ISC [Internal Security Council] meeting on 26 April.

“Meanwhile, David Marshall had reported of Outram prison that conditions were ‘radically worse than conditions imposed in the past either by the Imperial Government or by any previous Singapore Government’.”

(Excerpted from T.N. Harper ‘s”Lim Chin Siong and the ‘Singapore Story'” in Tan Jing Quee & Jomo K.S. (Ed.), Comet In Our Sky: Lim Chin Siong in History, INSAN, Petaling Jaya, 2001, pp.44-45. Additional contents in square brackets mine.)

..

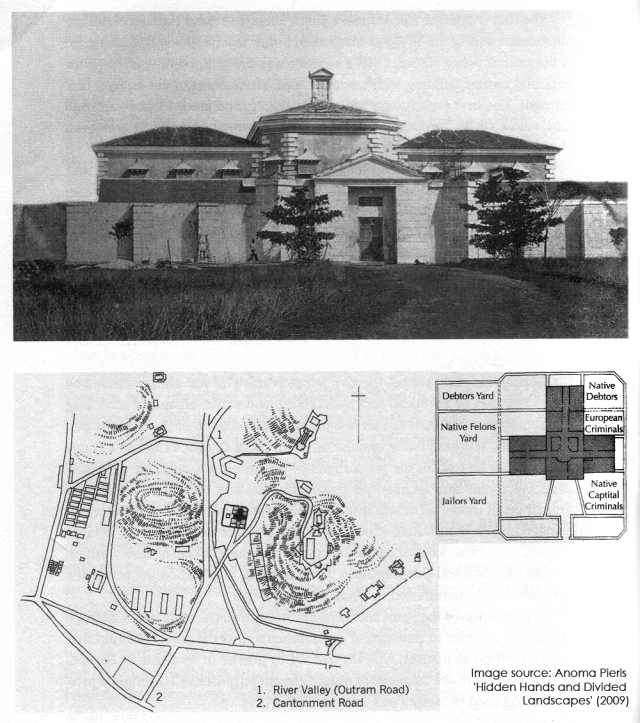

Design of new cellular wards for Europeans in the Outram prison, Singapore, 19th century. (PRO MPGG 1/17.2, UK: National Archives, Kew).

..

“[David] Marshall scored a minor coup against the government following the sweeping move to crush the left with Operation Cold Store, but in the end, he lost the battle. (…) Utilising a little-known statue that had been passed by the colonial government, Marshall discovered that he was able, as an Assemblyman, to demand acess to the [Outram] prison. The warden and the Solicitor-General, despite their reluctance, were finally forced to allow Marshall to visit the detainees, interview them and to report on their conditions to the Legislative Assembly:

‘In Singapore, as you will see from my report on the conditions I personally witness on the 23rd March 1963, male detainees are in small rooms in solitary confinement behind locked doors with a chamber pot in their own room, are not allowed out to visit the lavatory, have no chair, no table, a small 40-watt bulb high up in the ceiling, no writing material and not allowed to receive any newspapers or books from outside. The prison books are mostly infantile in character. Detainees arrested on 2nd February 1963 were not allowed to see a lawyer till 5th March.'(…)

“Following Marshall’s report, [the government] quickly moved the detainees to much more comfortable quarters at Changi, allowed them more time to exercise and socialise, and gave them access to reading matter and writing materials. From this time forward, Marshall remained in contact with Peter Berenson, the founder of Amnesty International. Singaporeans being detained under the PPSO [Preservation of Public Security Ordinance] and later the ISA were thus among the earliest of the political prisoners to be defended by that organisation. Marshall continued his fight against the manner in which the government exercised its powers under the ISA and the PPSO. Despite his efforts, these laws or similar measures remain on the books to this day.”

(Excerpted from Carl A. Trocki “David Marshall and the Struggle for Civil Rights in Singapore” in Michael Barr & Carl Trocki (Ed.), Paths Not Taken: Political Pluralism in Post-War Singapore, NUS Press, Singapore, pp.120-122. Additional contents in square brackets mine.)

..

Criminal prison, Outram Prison, Singapore 1881

(PRO CO 700/SS, National Archives, Kew [redrawn by Anoma Pieris].

..

“The Outram Prison was as infamous as its inhabitants. The British colonialists had, at one time or other, incarcerated almost all the nationalist independence fighters at Outram. From the end of the 1930s to the Japanese fascist army occupation from 1942 to 1945, to the return of the British colonialists to Singapore and Malaya at the end of 1945, Outram was the ‘premier’ prison for the nationalists.

“It is not difficult to name its alumni. Mentioned in the same breath in newspapers and history books include Ahmad Boestaman, Ishak Haji Muhammad, Dr Burhanuddin, all the leaders and main activists of the Kesatuan Melayu Muda (KMM), a radical Malay nationalist organisation under the leadership of Ibrahim Haji Yaakob, also Khatijah Sidek, Samad Ismail, Melan Abdullah and others. Members and supporters of the Communist Party of Malaya (CPM) and leaders of the anti-colonial labour movement from various ethnic groups also formed part of its famous alumni.”

(Excerpted from Said Zahari, The Long Nightmare: My 17 Years as a Political Prisoner, Utusan Publications & Distributors, Kuala Lumpur, 2007, pp. 33.)

..

Her Majesty’s Jail, a civil jail at the foot of Pearl’s Hill, Singapore 1848. Detailed plans and photograph.

Before the prison’s expansion in the 1880s.

..

《珍珠山上》

肖扬

像一阵狂风骤雨,

威迫着夜航的小舟。

我于人生的旅途上,

踏进了这罪恶的囚城。

让过去的光阴永远微笑吧,

记忆燃起了生命的火星,

我每天静听那教堂的钟声,

那牧师是否在为我祈祷黎明。

管什么十年八年的徒刑,

怕什么那一对对豺狼的眼睛,

谁能在虎口里去求得哀怜,

年青人的心决不会凋零。

远方的炮声不断地向我呼唤,

警报发出了末日的哀鸣,

隔着那重重的铁门哟!

我祈祷着自由的降临。

一九四二年秋于四排坡监牢A号拘留所

(四排坡监牢-Sepoy Lines Prison; refers to Outram Prison)

(摘自 《血碑增补本》,血碑增补本编辑委员会,香港,1997,pp.74-75.)

….

Photographs of the Outram Prison and Outram Park HDB Complex in absence;

and whatever that is latent around the Hill:

….

On an ending note (for the 50th anniversary of Operation Cold Store), I present the following photograph of the last page of a book I borrowed from the public library — — 《林清祥与他的时代》, which is the Chinese version of “Comet In Our Sky: Lim Chin Siong in History”. Someone has added two phrases to a poem dedicated to the late Lim Chin Siong…

阎王怕坏人,坏人还活着!

(The King of Hades fears the evil one. The evil one is still alive!)

‘坏人’ 是谁,我们心知肚明…

It’s time the victims of slander and repression are granted redress.

………

(to be continued in the next post “Victims of Slander, Police Courts and Speakers’ Corner“…)

The “Korban Fitnah” Location Scouting series:

This post is Part 1.

Part 2.

Part 3.

Part 4.

………………….