[Note: Otherwise stated, the film stills presented in this post are extracted from the following documentaries:

1. “Riding the Tiger” (2001), produced by the Singapore Ministry of Information and the Arts.

2. “The Undeclared War” (1998), produced for the BBC, directed by Robert Lemkin.

3. “SOE: Arms and the Dragon” (1984), produced by the BBC.]

Straits Times, 7 January 1946, Page 3

Guerilla Leaders Decorated by Supremo. Campaign Medals Awarded.

“On the wide stone steps of Singapore’s Municipal building, in which the historic surrender was signed, Admiral Lord Louis Mountbatten, Supreme Allied Commander, pinned the Burma Star and 1939-45 Star to the proud breasts of 16 leaders of the Malayan Resistance Movement, at an impressive ceremony yesterday. Three were Malays, the remainder Chinese.

In the uniform of the Malayan People’s Anti-Japanese Army, 11 saluted the Supremo with the clenched fist, Communist style.

Official spectators who were privileged to get a closer view of the ceremony saw the faces of these fearless men relax in a smile as the Supremo congratulated them. The other five gave the ordinary salute. Last to receive his decoration, Wang Siang Pu was conspicuously attired in an indigo blue uniform with a khaki cloth for headgear.

“Thousands of local residents and service personnel crowded round the enclosure at the padang in which stood the guard of honour formed by the 1st Battalion of the Cameronians (Scottish Rifles)…

“…They were entertained to 15 minutes’ martial music by the 52-piece band of the Royal Marines.

“Five minutes to the hour at which the Supreme Allied Commander was due to arrive, the guerillas, accompanied by Col. R. N. Broome [Richard Broome of Force 136] and another British officer drove up in four open cars, escorted by two traffic police motor cyclists and two M.P. motor cyclists.

“The crowd was hushed with impressive silence as the Supremo, preceded by a police pilot car and an escort of two police and two military police motor cyclists, stepped from his car to take the general salute as the clock tower [of the Victoria Memorial Hall] chimed noon.

“Followed by three staff officers and the officer commanding the guard of honour, the Supremo inspected the guard before making a speech expressing appreciation for the help given by the Malayan Resistance Army. He took opportunity also to explain the duties of South East Asian Command and what the Command had been able to do to relieve the food situation.

“Newsreel and Press cameramen, who had been busy shooting pictures for the last half hour, turned their cameras in the general direction of the Municipal steps as Col. Broome called out in Mandarin the names of the Chinese heroes to be decorated. It was a proud moment not only for these men but for the movement which they led with such success. Disbanded by not forgotten, Malaya’s resistance movement returned to take the credit which it so richly deserved.

“Not so well known in town, perhaps, as in the village and jungle, where their courage and gallantry had made them dreaded enemies of the Japanese, these honoured guerillas had come from all over Malaya to receive their decoration.

“Some were from Perak Central HQ of the Malayan People’s Anti-Japanese Army. Some came from Selangor, Negri Sembilan, Pahang, Kuantan and Johore. They represented thousands of their comrades up and down the Malay Peninsula, who suffered incredible privations and torture. Many of their members made the supreme sacrifice so that Malaya might be free.

“The 16 leaders of the Movement, decorated at yesterday’s ceremony were: Chen Ping, Liew Yau, Chan Yeung Pan, Lau Wei Chung, Fook Lung, Lao Wong, Chen Tien, Lin Chang, Chuan Seng, Siew Lit, Wu Chye Sin, Tan Siau Yau, Che Yeop Mahidin, Bahari, Abdullah bin Taami, Wang Siang Pu.”

(Source: Straits Times, 7 January 1946, Page 3. Additional information in italics and square brackets mine.)

….

Piqued by an interest in the Malayan resistance movement during the Japanese Occupation, I went in search of information regarding the 16 award recipients, based on the names in the list from the Straits Times report. The following is a summary of what I found out.

(The Straits Times report had provided rough romanised versions of the actual Chinese or Malay names of the award recipients. Therefore, I have included in my summary more popularly used versions of the names, and where appropriate, with chinese characters.)

The 16 “Burma Star and 1939-1945 Star” recipients:

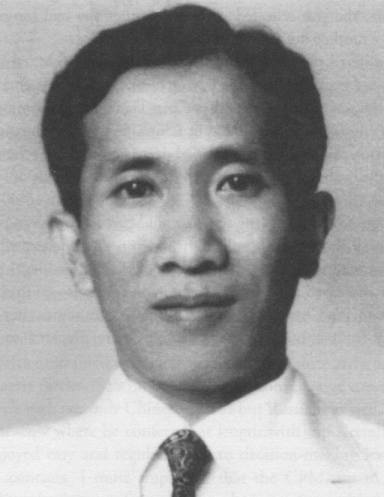

1. Chen Ping (Chin Peng, 陈平)

Member of the Malayan People’s Anti-Japanese Army (MPAJA) Central Military Committee (High Command) during the World War II Japanese Occupation. He was also the MPAJA’s Liaison Officer with Force 136 during the war.

Born in Setiawan, Perak in 1924, Chin Peng is a Fujian Hakka. He joined the MCP in 1940, and served as a Perak Local Committee member and Secretary of a Local Committee. He later emerged as the Secretary-General of the Communisty Party of Malaya in June 1947. From 1962, he directed the party from China.

Above: Chin Peng at the decoration ceremony in 1946.

Above: Chin Peng at the decoration ceremony in 1946.

Above: Chin Peng was dubbed “Public Enemy No. 1” and was the most wanted man by the British authorities during the Malayan Emergency between 1948 and 1960. A huge sum was offered for his capture and this was publicized in the Straits Times in May 1952.

Above: Chin Peng was dubbed “Public Enemy No. 1” and was the most wanted man by the British authorities during the Malayan Emergency between 1948 and 1960. A huge sum was offered for his capture and this was publicized in the Straits Times in May 1952.

Above: Film-still from “The Undeclared War”(1998). Chin Peng in the 1990s, living in exile in Hatyai, southern Thailand.

Above: Chin Peng and the other Burma Star recipients were treated to a gala cocktail party at the Government House (now the Istana) after the awards ceremony at the Municipal Building. Here, they were seen exiting the building. Walking ahead of Chin Peng (in the centre of the frame and looking in the camera) is Lau Yew, next in the list of the award recipients…

.

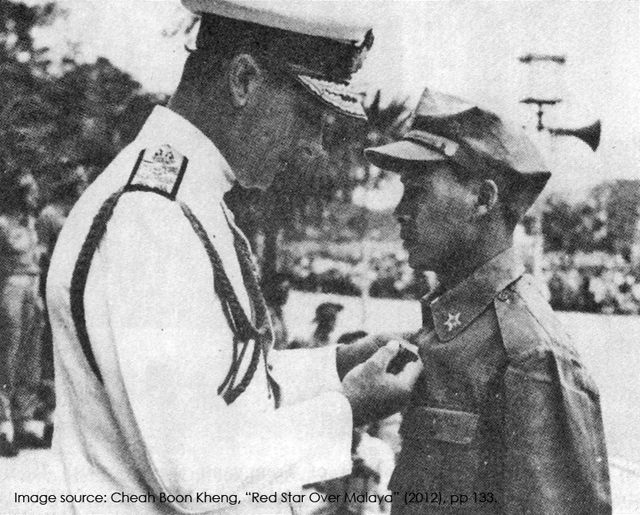

2. Liew Yau (Lau Yew, Liu Yau, 刘尧)

Chairman of the MPAJA Central Military Committee (High Command) during the war. ABA).

Born in Hainan Island in 1915, Lau Yew joined the CCP in 1931. In 1936, he travelled to Singapore to escape the nationalist government police. In July 1937, he joined the Anti-Enemy Backing-Up Society and directed one of its departments organised by shop clerks. He joined the MCP in Feb 1940 and received training at 101 Special Training School in Dec 1941 [More information about this school will be shared in a later post on a BBC documentary “SOE: Arms and the Dragon”. 101 Special Training School was set up by a British special operations branch based in Singapore, which was called ‘SOE’, short for “Special Operations Executive”.]

After the war, Liu Yau emerged as the president of the MPAJA Ex-Service Comrades Association and head of the Malayan People’s Anti-British Army (MPABA). He was later betrayed by his own bodyguard and killed in a police raid in Kajang, Selangor barely a month into the Malayan Emergency in July 1948.

Above: Admiral Mountbatten pinning the Burma Star and 1939-1945 Star on Liu Yau.

.

3. Chan Yeung Pan (Chow Yeong Ping, 周洋滨)

Commander, 1st Independent Regiment of the MPAJA Open Army at the end of the war. Headquartered in Ulu Yam, Selangor. He later defected to the British forces after the declaration of the (Malayan) Emergency in June 1948.

.

4. Lau Wei Chung (Liao Wei Chung, 廖伟中)

Commander, 5th Independent Regiment of the MPAJA Open Army at the end of the war. Headquartered in Simpang Pulai, Perak. Also known as Colonel Itu by Force 136 officers, so named because of his SOE radio call sign E-2.(SOE – Special Operations Executive, a secret WWII British special operations unit.) He was arrested at the start of the Emergency and banished to China, where he would die in the 1980s.

.

5. Fook Lung (Deng Fuk Loong, 邓福隆)

Commander, 2nd Independent Regiment of the MPAJA Open Army at the end of the war. Headquartered in Kuala Pilah, Negri Sembilan.

.

6. Lao Wong? (老汪)

I was not able to trace anyone by the name of “Lao Wong” among the Malayan resistance forces. But if I may speculate, it is possible that “Lao Wong” refers to Wang Ching or (Wong Ching, 汪清), commander of the 6th Independent Regiment of the MPAJA Open Army at the end of the war. Headquartered in West Pahang. This speculation is based on the fact that most commanders of the MPAJA Independent Regiments at the end of the war were named more or less accurately among the Burma Star recipients in the Straits Time report and in other scholarly writings, except Wong Ching and Lin Tian, the 3rd Independent Regiment Commander.

(24 Dec 2012; Update: I read in 郭仁德《神秘莱特》about some members of the MCP Pahang State Committee who were imprisoned by the British in Kuala Lumpur and were planning a prison escape before the Japanese invasion in 1941. And “老汪(清)” is one of those identified in the book. I surmised that this 老汪 a.k.a. 汪清, is the same MCP/MPAJA cadre that would receive the Burma Star from Lord Mountbatten in Jan 1946. So, my earlier speculation was indeed correct.)

.

7. Chen Tien (Chen Tian, 陈田)

Commander, 4th Independent Regiment of the MPAJA Open Army at the end of the war. Headquartered in Johore Bahru, South Johore.

Chen Tian was born in Singapore in 1923. In 1941, he joined the MCP. After the war, he became the Chief Editor of “Combatant’s Friend” (战友报), a newspaper published by the MPAJA Ex-Service Comrades Association. He became a member of the MCP’s Political Bureau, was concurrently Chairman of its Propaganda Department and participated in the 1955 Baling Conference and peace talks to put an end to the ongoing armed conflicts during the Malayan Emergency. In 1961 he went to China where he died in 1990.

.

8. Lin Chang?

Similar to the earlier speculations over the identity of “Lao Wong”, I was not able to trace anyone by the name of “Lin Chang” among the Malayan resistance forces, but I am guessing that “Lin Chang” may refer to Lin Tian (or 林田), commander of the 3rd Independent Regiment of the MPAJA Open Army at the end of the war. Headquartered in North Johore.

(This speculation may seem a little far fetched since “Chang” and “Tian” are obviously different and distinguishable. I made the guess because the other seven commanders of the MPAJA Independent Regiments at the end of the war (including “Lao Wong”, ie. Wong Ching, based on my speculation above) were listed among those presented with the Burma Star. It would be strange to leave the last regiment commander out of the recipient list. Besides, the Straits Times report had revealed that 11 of the award recipients “saluted with a clenched fist, Communist style.” The eleven were probably – 1 from the pro-communist faction of the Dalforce, namely Wang Siang Pu; 2 from communist-led MPAJA Central Military Committee, namely Chin Peng and Liu Yau; and following the thread of my argument, all 8 MPAJA Independent Regiment Commanders. Therefore, I dare say that “Lin Chang” in the Straits Times report actually referred to “Lin Tian” the 3rd Regiment Commander. It could have been an error on Straits Times’ part.)

.

9. Chuan Seng (Chuang Ching, 庄清)

Commander, 7th Independent Regiment of the MPAJA Open Army at the end of the war. Headquartered in Sungei Riau, near Kuantan, Pahang.

.

10. Siew Lit (Ho Siew Lit, 何小力)

Commander, 8th Independent Regiment of the MPAJA Open Army at the end of the war. Headquartered in Kedah.

.

11. Wu Chye Sin (吴再新, alias Wu Beng Chye)

A member of Force 136, a special operations unit under the command of SOE, tasked to carry out sabotage of a limited tactical nature in enemy occupied territories. He participated in Operation Gustavus I, the first infiltration mission conducted by Force 136, aimed at seting up an espionage network in Malaya. They first landed on Pangkor Island, Perak, in May 1943.

He was recruited by Lim Bo Seng, and underwent training in Chung King, China and Poona, India at the Eastern Warfare School.

.

12. Tan Sian Yau (Tham Sien Yen, 谭显炎, alias Han Lay Boon)

A member of Force 136. He also participated in Operation Gustavus I.

.

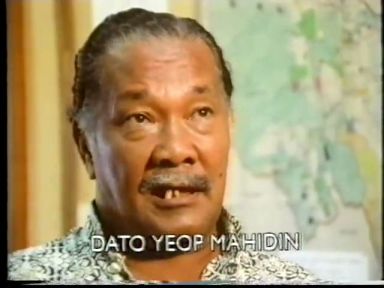

13. Che Yeop Mahidin (Yeop Mahidin bin Mohamed Shariff)

Leader of Pahang Wataniah (or Gerila Wataniah Pahang). Before the war, he was an Assistant District Officer in Kuala Lipis. When World War II broke out, he formed an anti-Japanese resistance group called the “Pahang Wataniah”, which had a strength of about 250 men and was assisted by Force 136, which assigned Major J. D. Richardson to help train the unit. He later helped establish the Rejimen Askar Wataniah, the military reserve unit of the Malayan Army.

He is also the cousin of Abdullah CD (Che Dat Anjang Abdullah), who was once a member of KMM (Kesatuan Melayu Muda) but later fought under the MPAJA, and became a Malay MCP leader, in command of the 10th Regiment of MNLA (Malayan National Liberation Army) in Temerloh, Pahang.

.

14. Bahari (Haji Bahari bin Haji Sidek)

A member of the Malay Section of Force 136. He was a student in Mecca before World War II broke out, and had been recruited by Force 136 in India and became an agent under the Malay Section of Force 136, which was headed by Major Tengku Mahmood Mahyideen, a son of the last ruler of Pattani. As opposed to Wu Chye Sin and Tham Sien Yen who had arrived by submarine when they infiltrated Malaya, Haji Bahari parachuted into the Malayan jungle in Grik, Perak.

.

15. Abdullah bin Taami?

(named as “Abdul Abdullah bin Ta’ani” in other sources, such as “colonialfilm.org.uk”.)

I still have no idea who he was.

.

16. Wang Siang Pu?

A member of Dalforce, a Singapore Chinese volunteer army which had fought the invading Japanese forces in Feb 1942 before the British surrender. I had briefly written about Dalforce in an earlier post.

Besides being singled out in the Straits Times report for donning an indigo blue uniform and with a khaki cloth for headgear (which was the standard attire for Dalforce soldiers), “Wang Siang Pu” had not appeared in any of the resources that I have accessed during the writing of this post. Guess I have to read more then….

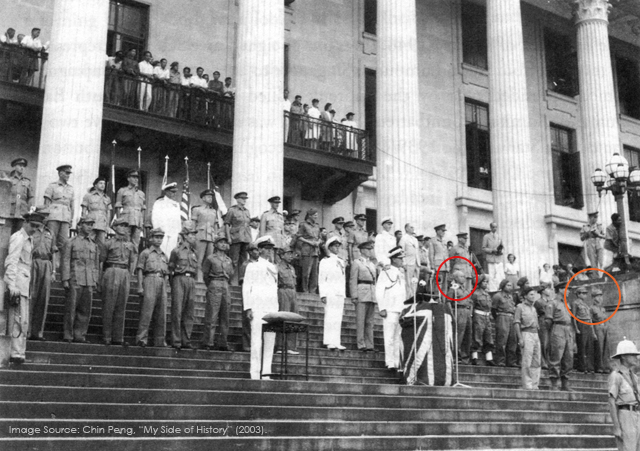

Above: A photograph of Admiral Mountbatten and the medal recipients on the steps of the Municipal Building (now the City Hall). The person with the distinctive headscarf that I have marked with a red circle is Wang Siang Pu from Dalforce. The ten representatives of MPAJA are the eight soldiers that stood on the left side of the photograph and the last two on the right which I have marked with an orange circle. All ten of them wore the MPAJA uniform with the five-cornered cap. The remaining five recipients from Force 136 and other Malay resistance movements wore berets.

….

In Chin Peng’s “My Side of History” (published in 2003), he gave an account of his experiences with regards to the decoration ceremony at the Municipal Building on 6 Jan 1946:

“The BMA [British Military Administration] booked us into lavish accommodation at the famed Raffles Hotel. On January 6, escorted by motorcycle outriders, we were driven a short distance down the road, past St. Andrew’s Cathedral, to the Municipal Building, now the City Hall. There, the Royal Marine Band was already playing. In our military uniforms, we were ushered to a position on the padang immediately in front of the Municipal Building steps. A British flag-draped podium had been placed in the centre of a landing halfway up the flight of steps that led to the building’s main doors. To the left of the podium stood a small table on which rested a cushion. On top of the cushion lay our medals.” (Additions in italics and square brackets mine.)

Chin Peng was rather critical of the BMA’s intent for such an awards ceremony:

“Why, you might ask, had the British gone to so much expense and trouble to honour us so publicly, nearly five months after Japan’s surrender? After all, on September 12, 1945, 16 of our guerrillas had already participated — prominently positioned — in the official victory celebrations staged at the same venue. [I wrote about the event with accompanying archival film-stills in an earlier post.] Furthermore, arrangements had been finalised for a special MPAJA contingent to participate in the June 8, 1946, Victory Parade in London. Was this January 6 display another propaganda exercise? Was it aimed at smothering us with attention in the hopes our resolve to pursue an anti-colonial stand would be undermined? If so, Admiral Mountbatten and his High Command had been badly advised.” (Additions in italics and square brackets mine.)

And Chin Peng was also indignant that they, the MPAJA representatives, were treated in a similar fashion to the pro-Kuomintang Force 136 agents or resistance “fighters”, that they had received decorations identical to the MPAJA representatives:

“On hand with us outside the Municipal Building that morning were two Kuomintang Chinese, three Malays and a single Chinese Dalforce representative in separate groupings. They were to receive decorations identical to ours. Was this some kind of misguided gesture demonstrating Britain’s willingness to treat all political persuasions equally? Or get things racially correct? Declassified documents now reveal that it was John Davis [of Force 136] who had pressed for CPM [Communist Party of Malaya] operatives to be given awards immediately after the cessation of hostilities. But it had taken the system a long time to become convinced about the merits of Davis’ suggestion. His idea was not popular when first presented. In all probability it would have been shelved had civil disturbances throughout Malaya not been on the increase. Some quarters must have decided matters would improve if we got placated.” (Additions in italics and square brackets mine. Emphasis in italics mine.)

…

By Chin Peng’s suggestion, the awards ceremony is conjured up as a propaganda exercise by the British with the intention to placate the Malayan Communist Party and their united front organisations, and attempt to alleviate anti-colonial sentiments. But the British had to accommodate other factions in the WWII resistance movement in the awards ceremony so that they cannot be accused of bias. I mean, surely they cannot be seen to forsake locally-born operatives under Force 136’s command, a British-directed special ops organisation. If Burma Stars are to be awarded to the MPAJA soldiers, the British are obliged to offer the same Stars to their very own Force 136 members, though the British must have surely acknowledged, behind the scenes, that the communist-led MPAJA was the most, if not the only, potent Malayan resistance force to be reckoned with during the Japanese occupation.

So, who are the MPAJA, the Malayan People’s Anti-Japanese Army, the WWII Malayan resistance group at the centre of the events of which the filmic, pictorial and textual information this post is attempting to present?

I have compiled a series of quotes from numerous sources that attempt to uncover, especially for myself, a student of Malayan/Singaporean political history, what constitutes the MPAJA, their motives and intents, their role in history and their relationship with the colonial masters whom they had to join hands with to fight the Japanese, but ultimately contend with for political control over the Malayan peninsula…

..

《马来亚人民抗日军战记》

- 马来亚人民抗日军退伍同志会总会稿,1946年8月5日。

“马来亚人民抗日军是马来亚全面沦陷后,马来亚人民抗日武装队伍。它由马来亚各民族优秀儿女所组成,包括着各党派,各阶层的抗日人士,在马来亚人民抗日同盟会及马来亚共产党协助之下,展开敌后的抗日游击战争。

“一九四一年年底,当日军步步逼近霹雳怡保的时候,马来亚共产党认为组织马来亚人民敌后游击战争,配合英军前线的军事行动是非常有意义的,于是,就在马来亚共产党号召之下,各州人民就有计划的准备组织起来,同时有一百六十五个优秀的民族儿女(多数是华侨爱国青年)自告奋勇,首先报名集中新洲,经短期训练之后,先后分批深入雪兰尔,森美兰及柔佛,团结和训练人民,建立起人民抗日军第一,二,三和四独立队来。

“马来亚沦陷之后,这四个独立队,在万分艰难的环境下,在物资短缺,疾病侵袭的种种威胁之下,靠着马来亚人民积极的支持,坚决的领导着人民,展开抗日斗争。整个敌后的抗日斗争环境广泛的发展起来,人民抗日军的组织也逐渐扩大,抗日的队伍普遍了全马。人民抗日军的组织从四个独立队发展到八个独立队。以下就是人民抗日军各独立队成立的日期和战斗的地区:

第一独立队 1942年1月1日 雪兰尔州

第二独立队 1942年1月11日 森美兰州

第三独立队 1942年1月20日 柔佛州北部

第四独立队 1942年1月30日 柔佛州南部

第五独立队 1942年12月1日 霹雳州

第六独立队 1943年8月13日 彭亨州西部

第七独立队 1944年9月1日 彭亨州东部

第八独立队 1945年8月初 吉打州

“这八支人民抗日武装队伍,包括全马各民族爱国份子共约七千名。这八支队伍自从成立以后,就成为日寇心腹之患。此外,抗日的人民自己组织的抗日自卫团,抗日后备队,更团结着城市乡村成千成万的民众。”

(摘自《大战与华侨》, 新加坡南洋出版社,1947年。)

..

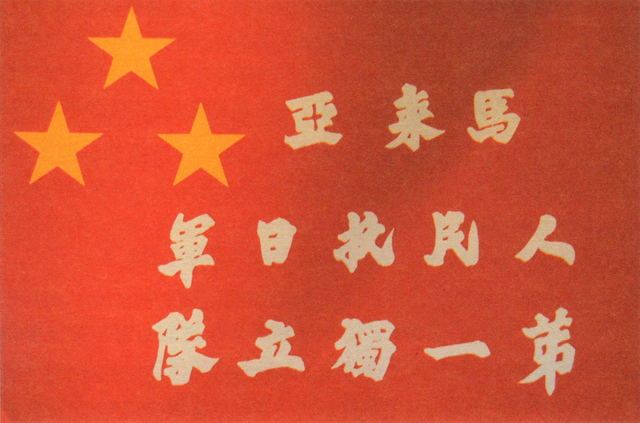

The three-star flag of the MPAJA 1st Independent Regiment. The MPAJA is also popularly known as the “Bintang Tiga” army (Bintang – Star; Tiga – three).

..

“Not long after the outbreak of war in the Far East, the Malayan Communist Party (MCP) had put up a proposal to the Government that the Chinese should be allowed to form a military force to fight the Japs, and that it should be armed by the British. The C.-in.C. (Commander-in-Chief) at first refused to allow this, but as the war situation rapidly deteriorated he eventually gave permission for the organisation (SOE; Special Operations Executive) to train and use a certain number of Chinese selected and supplied by the Malayan Communist Party. Where necessary, sanction for their release from jail for this purpose was also given.”

(Source: Spencer Chapman,The Jungle is Neutral, 1st edition 1997, Marshall Cavendish Editions, Singapore, 2009. pp. 13. Additions in italics and parenthesis mine.)

.

“Because of its anti-Japanese policy, the MCP was well placed to exploit the situation to its advantage when the Japanese attacked Malaya on 8 December 1941. The MCP immediately repeated its offer of aid to the British. After Japanese troops made a rapid advance in Malaya, secret contacts were established between MCP officials and the British police, during which they discussed terms including the release of communist detainees. The underground MCP came out publicly in a statement to support British defence measures, and its supporters vied with those of the Kuomintang to exhort Malayan Chinese to renew their pledges of assistance to the British. In this campaign Tan Kah Kee, the pro-left Singapore Chinese leader, took the lead. Communists joined with other Chinese groups to call on the government to raise a Chinese militia to assist in the defence of Singapore. As British military reverses were reported, including the sinking of the British warships Prince of Wales and Repluse, the British government and the War Office in London gave approval to accept the MCP offer. On 15 December some leftist political prisoners were released from detention.(…)

“On 18 December, when the MCP had still not heard from the British authorities, the Central Executive Committee held a meeting in Singapore and decided to “go ahead and rely on the people’s efforts alone” in mobilizing a local defence force. That very day, the British contacted the MCP and accepted its offer.”

(Source: Cheah Boon Kheng, Red Star Over Malaya: Resistance and Social Conflict During and After the Japanese Occupation of Malaya, 1941-46, 4th edition, NUS Press, Singapore, 2012. pp.59. Emphasis in italics mine.)

.

“Down in Singapore there followed a frantic rush to salvage whatever was possible of the CPM offer (Communist Party of Malaya, otherwise known as MCP or Malayan Communist Party). Special Branch senior officer, Innes Tremlett, who spoke fluent Cantonese and was the controller of agent Lai Te (Secretary General of CPM but an agent of the British), arranged the December 19 (1941) Geylang rendezvous between the CPM Secretary General and the SOE’s Frederick Spencer Chapman (…). Also present at these crucial deliberations was Special Branch Police Inspector Wong Ching Yok. The meeting took place in a room above a charcoal dispensing shop used as a Party safe-house.

“The SOE, operating in Singapore under the cover name Oriental Mission, offered to accept as many communist recruits at its 101 STS (Special Training School) on the island (Singapore) could accommodate. Chapman, at that time, was the commanding officer of the school. The British further agreed that those communists under arrest and wishing to volunteer would be promptly released from jail. The first of a series of courses would begin on December 22 at the school’s Tanjong Balai headquarters, a commandeered mansion located on a small promontory at the mouth of the Jurong River.(…)

“The plan was to train and arm these volunteers to operate in guerilla units. Where possible, they would be placed in jungle hideouts ahead of the Japanese advance.”

(Source: Chin Peng, My Side of History, Media Masters Pte Ltd, Singapore, 2003. pp.65. Additions in italics and parenthesis mine.)

..

Lai Te (or “Lai Teck”; 莱特), Secretary-General of the Malayan Communist Party (1939-1947). He was also an agent for the British Detective Bureau and during the Japanese Occupation years, an agent for the Japanese Military Police, the “Kempeitai”. An elusive figure by most accounts, he had been branded as a traitor by many MCP cadres and was rumoured to be murdered in Bangkok for his misdeeds.

..

“On 21 December the training of the MCP recruits at 101 STS began. Individual courses lasted ten days and a total of seven classes, consisting of 165 enthusiastic party members selected by the MCP, rushed through the training programme. The graduates became the nucleus of the MPAJA.

“The original British plan was for each MCP “stay-behind” party to be led by a British officer to ensure that British instructions and policy were carried out. However, owing to the rapid advance of the Japanese, this was not possible and the first class of MCP graduates of 101 STS was hurriedly sent out to Selangor in early January to work on its own. The second class went to Negri Sembilan and the third to north Johor. The fourth and final classes infiltrated through Japanese lines into south Johor on 30 January 1942. Each group eventually established liaison with the State Committee of the MCP in the area where it operated. From March onwards the groups were recognized by the MCP’s CEC (Central Executive Committee) as the First, Second, Third, and Fourth Independent Regiment of the MPAJA respectively.”

(Source: Cheah Boon Kheng, Red Star Over Malaya: Resistance and Social Conflict During and After the Japanese Occupation of Malaya, 1941-46, 4th edition, NUS Press, Singapore, 2012. pp.61. Emphasis in italics; additions in italics and parenthesis mine.)

.

“The 165 communist graduates of the 101 STS thus formed the first organized military force of the Malayan People’s Anti-Japanese Army as well as the backbone of the guerrilla army after 1945. The first four regiments were as follows:

First class of 15 men – the 1st Independent Regiment

Second class of 35 men – the 2nd Independent Regiment

Third class of 60 men – the 3rd Independent Regiment

Fourth class of 55 men – the 4th Independent Regiment

(…)

“Despite being born admist the disintegration of British defence the MPAJA went on to put up what was often the only armed resistance against the Japanese occupying forces and their collaborators. The Japanese were from the start aware of the potential problems that the guerrillas would pose. Immediately after the occupation of Singapore many frontline troops were transferred ‘upcountry’ to Malaya for mopping up and anti-guerrilla operations.”

(Source: Ban Kah Choon & Yap Hong Kuan, Rehearsal for War: Resistance and the Underground War against the Japanese and the Kempeitai, Horizon Books, Singapore 2002. pp.102. Emphasis in italics mine.)

..

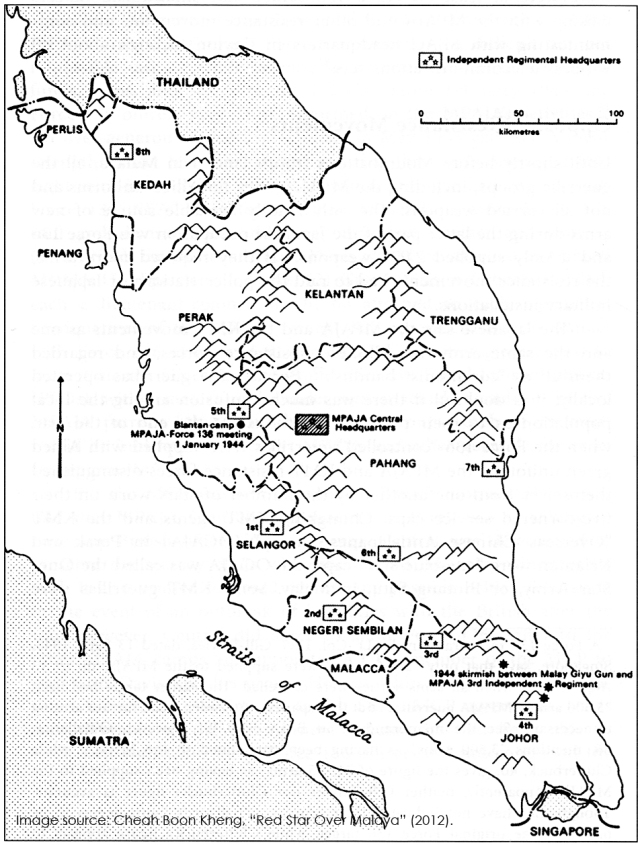

Locations of the eight Independent Regiments of the MPAJA.

Locations of the eight Independent Regiments of the MPAJA.

..

“These regiments were called independent units as each of them was an independent operational unit functioning in a strategically defined and specific area. Complete operational freedom was given to the regimental commander who was expected to conduct operations within his zone according to the political, military and geographical terrain of his area. A regiment was in turn divided into anything from two to five companies. Each of these was also given the same operational freedom of manoeuvre although a certain amount of control was maintained through the regimental headquarters. Day-to-day operations were, in fact, carried out at the company level for the most part. These companies were designated as patrols. (…) Each Independent Regiment with its five to six patrols comprised between 400 and 500 men.”

(Source: Ban Kah Choon & Yap Hong Kuan, Rehearsal for War: Resistance and the Underground War against the Japanese and the Kempeitai, Horizon Books, Singapore 2002. pp.117.)

..

..

“马来亚人民抗日军在三年八个月的抗日战争中,大致经过了三个阶段:

第一阶段即第一年是最困难的一年,也是防御敌人,站稳脚根的一年。日军占领全马后,就以检证大屠杀来胁迫人民服从他的野蛮统治,并宣扬它的“赫赫战果”,用欺骗手段蒙骗落后群众,掩饰其强盗面目。当时群众还未广泛发动起来,也缺乏武装斗争的经验,致使抗日军遇到许多困难:一是给养不足,头一、二个月,还有英軍留下的石灰米可吃,以后吃的是番薯、木薯、粟米、黃梨和野菜,甚至以井水、河水充飢。二是,住在森林中不服水土,不适应山岚瘴气。由于营养不足,虐疾、伤寒、水肿烂腳、疮癞等疾病丛生,许多同志因缺医少药被夺去了生命。据統计,因患病而死亡的同志約占抗日军牺牲总人数的三分之一。三是,要应付敌人的頻繁进攻和扫蕩。为了反击敌人的扫蕩,抗日军也常常出动袭击日军,在战斗中不少优秀的指挥員和英勇的战士牺牲了。如当时五个独立队的第一任司令部人员,就有的80%的人牺牲或被捕。因此,建队的第一年,各独立队的領导变动很大。(。。。)

“第二阶段由1943年中至1944年中,这段时期主要在人民群众中组织了“抗日同盟会” [MPAJU; Malayan People’s Anti-Japanese Union]、“抗日后备队”,他們积极为抗日军筹措资金、粮食(主要是杂粮)、医药等,基本扭转了粮食、药物供应的困难。同时,抗日军从战爭中学习战争,建立了较为稳定的根据地,因此在战斗上,不但能对付日军的扫蕩,也能组织力量进攻日军据点。(。。。)

“第三阶段,即从1944年下半年开始,抗日军由被动转为主动,农村中普遍建立了抗日同盟会、抗日后备队、锄奸等组织,广大农村为抗日军所控制,日军龟缩在城镇,不敢轻易进入农村骚扰,日军在许多地区开始強迫群众在城镇四周修筑防御工事,以防抗日军袭击。抗日军乘此有利形勢,在各地頻繁伏击日本军车,把打击重点转移到中小城鎮,袭击警察局和日军兵营。到1945年秋,抗日军正计划与联军配合大举歼灭敌人之际,日本却宣布无条件投降了。”

(摘自:曾冠彪《人民的抗日劲旅:简述“马来亚人民抗日军”》; 收录于:新马侨友会编,《马来亚人民抗日斗争史料选辑》,香港见证出版有限公司出版,香港,1992,pp.7-8.)

.

“During the first year and a half of its existence, the MPAJA fared badly, lacking food, capable leadership, and sufficient training and experience in guerrilla warfare. Japanese terrorism prevented people of all races from helping the guerrillas. One-third of the guerrilla force was said to have died during this period.

“The second period, from mid-1943 to mid-1944, saw the MPAJA improve its organization, food supplies, communications system, and military training; consequently, it was said to have increased four times in size.

“The third period, from mid-1944 until the end of the war, was one of consolidation and growth and the establishment of close MPAJA-Allied cooperation. The MPAJA henceforth received supplies of arms, medicine,, and money from the headquarters of the South East Asia Command (SEAC) under Admiral Mountbatten based in Colombo.”

(Source: Cheah Boon Kheng, Red Star Over Malaya: Resistance and Social Conflict During and After the Japanese Occupation of Malaya, 1941-46, 4th edition, NUS Press, Singapore, 2012. pp.61-62.)

.

“1943年2月,马共在雪兰莪州召开三中执委会,有部分党、军代表參加,会议决定了党在抗日民族解放战争时期的三大任务,正式通过了“抗日九大纲领”. “抗日九大纲领” 第一条就是“驱逐日本法西斯出马来亚,建立马来亚民主共和国”。此外,还制定了马来亚人民抗日军的军旗、军帽、军礼、军歌、军纪等。以紅花大地綴三顆金星为军旗(左上角三顆金星象征马来亚马、华、印三大民族团結一致),以五角型帽顶、前配三顆紅星军帽,以举右手握拳齐额为军礼,以西班牙反法西斯战歌“紅旗歌”为军歌。抗日军的军纪在各独立队成立时已先后制定了出来。在这次会议中统一规定了四条紀律:一、絕对服从指揮。二、严守军事秘密。三、没收敌产归公。四、愛护群众利益。同时也制定了八项注意。以上这些决定,使马来亚人民抗日军有了明确的政治纲领和最高行动准则,使部队有了統一的旗帜、标志和严明的紀律。”

(摘自:曾冠彪《人民的抗日劲旅:简述“马来亚人民抗日军”》; 收录于:新马侨友会编,《马来亚人民抗日斗争史料选辑》,香港见证出版有限公司出版,香港,1992,pp.6.)

..

Film-stills from BBC’s “The Undeclared War”. MPAJA soldiers wore five-cornered caps sewn with three red stars, which represented the three major races of a unified Malaya that communist literature extolled – the Chinese, Malays and Indians. And they saluted with a clenched fist.

..

“There was no class distinction in the MPAJA. The common form of address was “comrade”. Even the chairman of the Central Military Committee was addressed as comrade, but discipline was tight. Though the MCP organized the MPAJA, many of its members were not communists. The link between the MCP and the MPAJA was political education.

“An MPAJA camp usually emphasized military practice and drilling, political education, cooking, propaganda, collection of food supplies, and cultural affairs. Mandarin, the Chinese national language, was the lingua franca of the MPAJA and was used in all correspondence and official statements. Concession to the Malay, Tamil and English languages were made in some of the propaganda newssheets published by the MPAJA’s propaganda bureau.”

(Source: Cheah Boon Kheng, Red Star Over Malaya: Resistance and Social Conflict During and After the Japanese Occupation of Malaya, 1941-46, 4th edition, NUS Press, Singapore, 2012. pp.65.)

..

Film-stills from BBC’s “The Undeclared War”. Re-enactments of life in an MPAJA camp. Military practice, drilling and political education.

..

“The MPAJA’s main link with the local population in the areas where it operated was the Malayan People’s Anti-Japanese Union (MPAJU). The MPAJU fed the guerrillas, raised funds, collected clothes, fighting materials, food, and gathered intelligence. It also arranged guides to take MPAJA patrols through unknown territory and formed corps of couriers. The MPAJU pursued an “open” policy of recruiting people of all races, classes, religions, and political creeds who were opposed to the Japanese regime. It therefore absorbed Chinese (who constituted the majority of its supporters) but also aborigines, Malays, Indians, and others. It welcomed within its ranks businessmen, KMT members, Chinese secret society members, and even government officials.”

(Source: Cheah Boon Kheng, Red Star Over Malaya: Resistance and Social Conflict During and After the Japanese Occupation of Malaya, 1941-46, 4th edition, NUS Press, Singapore, 2012. pp.67. Emphasis in italics mine.)

..

An MPAJA/MPAJU recruitment poster.

“参加游击队,打日本鬼子去!” (Join the Guerrillas, Fight the Japanese Devils!)

..

“On 24 May 1943 the first Force 136 reconnaissance party, consisting of Col. John Davis and five Chinese agents, arrived in a submarine off the Perak coast and landed in Malaya. This operation was code-named Gustavus I. Other groups were introduced in the same manner, in operations Gustavus II, III, and IV, the last taking place on 12 September 1943. Besides Davis, the other officers were Capt. Richard Broome and Maj. Lim Bo Seng, a Malayan KMT member and agent of the Chinese government in Chungking. Their subordinate staff was all KMT Chinese trained in wireless operations and intelligence work. Force 136 was attempting to set up its own intelligence service by using KMT agents. This is evident because only after the KMT agents had been established in cover jobs in Ipon was contact made on 30 Septmber with Chin Peng, presentative of the Perak MPAJA headquarters.”

(Source: Cheah Boon Kheng, Red Star Over Malaya: Resistance and Social Conflict During and After the Japanese Occupation of Malaya, 1941-46, 4th edition, NUS Press, Singapore, 2012. pp.75.)

..

Film-still from BBC’s “SOE: Arms and the Dragon”. Force 136’s John Davis (center), Tham Sian Yen (left), and Wu Chye Sin.

Film-still from BBC’s “SOE: Arms and the Dragon”. Force 136’s John Davis (center), Tham Sian Yen (left), and Wu Chye Sin.

Film-still from the documentary “Riding the Tiger”. A Force 136 soldier, wearing the round badge with the Force 136 crest on his sleeve.

Film-still from the documentary “Riding the Tiger”. A Force 136 soldier, wearing the round badge with the Force 136 crest on his sleeve.

..

“On 1 January 1944 Lai Tek and Chin Peng, both representing the MCP, MPAJU, MPAJA, arrived at the Force 136 camp and held talks with the three Force 136 officers (Davis, Broome and Lim Bo Seng), who had now been joined by Major F.S. Chapman, a member of one of the original “stay-behind” teams left in Malaya after the fall of Singapore and who was co-opted into the Force 136 team. The three Force 136 officers described themselves as representatives of Admiral Mountbatten, the British Supreme Allied Commander for Southeast Asia.

“It was agreed that in return for arms, money, training and supplies the MPAJA would cooperate with and accept the British Army’s orders during the war with Japan and in the period of military occupation thereafter. The British also agreed to finance the MPAJA with 150 taels of gold (about 3,000 British sterling a month) and instructed that all arms would have to be handed back after the Japanese defeat. The policy of Southeast Asia Command, which controlled Force 136, was to arm the guerrillas, place them under the control of British officers, and prepare them for the time of an Allied invasion. Political matters were excluded from the agreement. Both sides agreed that no question of post-war policy would be discussed.”

(Source: Cheah Boon Kheng, Red Star Over Malaya: Resistance and Social Conflict During and After the Japanese Occupation of Malaya, 1941-46, 4th edition, NUS Press, Singapore, 2012. pp.75.)

.

“1943年5月,联军用潜艇送約翰•台維斯等6人在霹雳州邦咯岛附近登陆,与抗日军取得联系,使他們的安全得到保证。随后还有二批乘潜水艇霹雳和柔南登陆,他们均在人民抗日军的保护下开展情报活动。明确地说,如果没有强大的人民抗日军的保护,他們不但情报工作不能开展,而且连能否生存下去也成为問題。

“1944年1月1日,马共和抗日军派出代表与联军东南亚总部代表台维斯等三人会谈,初步拟定出共同抗日的協议,联军方面答应供给人民抗日军装备、资金、药品和给养,但声明派遣来马的136部队人员不参与战斗任务,如遇日军扫荡,则由抗日军负责抵抗回击;人民抗日军則答应配合联军反攻日军。后來由于他們的谍报中心被日军破获和电台失灵,失去了与駐印度的联軍总部的联系,

“这个协议延至1945年2月才由联军总部核准,隨后即用空军投了几批136部队的联络官和华人情报员、电讯员以及电台等物资。5月份起空投武器、物資.”

(摘自:曾冠彪《人民的抗日劲旅:简述“马来亚人民抗日军”》; 收录于:新马侨友会编,《马来亚人民抗日斗争史料选辑》,香港见证出版有限公司出版,香港,1992,pp.9.)

..

Film-still from BBC’s “SOE: Arms and the Dragon. Weapons and supplies are air-dropped into the Malayan jungle for MPAJA and Force 136’s retrieval and use.

Film-still from BBC’s “SOE: Arms and the Dragon. Weapons and supplies are air-dropped into the Malayan jungle for MPAJA and Force 136’s retrieval and use.

..

“1944年10月,面临配合联軍反攻马来亚、人民抗日軍应如何部署的問題,马共召开了全马的党、军高級干部非常会议,出席的有各州党的最高负责人和各独立队司令部代表。会议除了綜合分析各州政治军事情况、交流战争经验之外,主要针对如何与英军合作,配合反攻,和实现国家独立等問題作了决定。

“会议还要求各独立队扩大队伍,抽调少量干部战士作为基础,大量吸收后备队員(或自卫队员)入伍,成立新队,接受英军联絡官驻队,成为与英军合作的部队(称为新队); 原有的队伍(称为老队)不与英军接触,保持其独立性,另建立參謀本部領导;

“各州加緊开办军政干部训练学校,培养地方军事、行政管理人才;筹建民族解放同盟,为实現马来亚國家独立做准备。因此,1945年2月联军空投136部队人员來马后,老队沒有公开出來。与他们合作建立的新队,不设党代表,也称马来亚人民抗日军,独立队番号不变,并无136部队之称。英军派三至四名136部队人员当联络官,负责抗日军与联军总部联系。人事调动服从老队安排,军事行动表面上服从联絡官传达联军总部命令,但具体行动仍接受老队指挥。这二支队伍,至日本投降前夕,各有八个独立队,所辖中队和人数如下:

“老队共48个中队,独立分队有2个,人数約5400人。 新队共21个中队,人数約4500人。 以上中队合计69个,人数約9900人,加上遍布全马各州的抗日后备队、自卫队等武裝组织,共約15000人.”

(摘自:曾冠彪《人民的抗日劲旅:简述“马来亚人民抗日军”》; 收录于:新马侨友会编,《马来亚人民抗日斗争史料选辑》,香港见证出版有限公司出版,香港,1992,pp.10.)

..

LOCATION SCOUTING IN ARCHIVE FOOTAGE OF THE IMMEDIATE EVENTS FOLLOWING THE JAPANESE SURRENDER IN 1945:

Part 1 – The Surrender.

Part 2 – The Parades.

This is Part 3 – The Decoration Ceremony.

…………..